Identity Crisis

This issue reflects 8 weeks of dedicated by the Summer 2025 Writer’s Block Ink Creative Workshop participants work and communal creativity. Each piece was created with the theme of struggling within identity, keeping in mind how creativity and expression can help us to heal and develop as conscious people.

The complete text is available here, but the zine itself is only available by purchase either in our shop or in one of the bookshops that carries it!

Currently Available at:

Fiddleheads Co-Op, New London

Quimby's Book Store, Chicago

A Natural Reserve

By Moss F.M.

In a misty wood on a sun dappled morning, a group of gnomes forage fruit, flowers, mushrooms, and herbs. This trite scene would be idyllic if Jarold wasn't such a prick. Indeed, all would be having a lovely morning if he was absent.

As if cued, the thorny gnome begins the return journey from his area of a briar patch with his quota: no more, no less. He nitpicks Marta's paltry basket under his breath, scoffs at Edmund's poor flirtation of Marta, and rolls his eyes at Mrs. Bellowstones’ grumbling about achy joints.

Jarold sticks to a traditional pathway designed to hide gnomish tracks from outsiders. Humans relinquished dwelling here for their clamoring concrete cities generations ago. They retreated from the wilds and knit wires, abuzz with electricity and voices, through trails cut by their ancestors. Naught but petty gnomish squabbles disrupt trilling bird song, guttering creeks, the susurration of leaves and grasses. It's a peacefulness that verges on monotony.

For those who know where to enter, the foliage breaks into the village of Oakvale. Morning market bustles cheerily with stands of forageables, produce, textiles of earthen tones (and occasionally jewel tones for a higher price). Baked goods perfume the air, joining cloying florals and musky livestock. Those not haggling laugh and gossip around the gazebo and a garish ribbon-banded maypole.

Jarold arrives well before the other gatherers. He enters dismally and makes no effort to avoid shoppers and mongers. Any that don't shuffle out of his impertinent pathway are shoved into stands of sparkling trinkets and fish. He drops the berry basket unceremoniously on the table where Uncle Benton gives a pinched smile to an irritated spinster.

“Ah, nephew —” he starts, caught between soothing the flustered old windbag and winding up to ‘chastise’ Jarold. Jarold is already turning away.

“The others will deliver before lunch, if only not to miss a meal.” He waves dismissively, secure in his nepotism and disdain for the pleasantries of town. “Going back to watch duty.”

Jarold follows the path carved by his first passing, ignoring meager glares and meeker “excuse you’s!” He turns off the hidden trail to forge his way to seclusion.

As the distance grows between Jarold and jostling lines of goods and buyers, his shoulders inch down little by little. SIGH. Ah, better.

The blessed solitude of the woods! No blathering fools to manage, no childish festivities and social interactions to navigate, no expectations here. He prefers to contribute to the community via unaccompanied watch duties at the perimeters of their home forest — when his uncle isn’t volunteering him to group work for “social skill building.” Ugh.

Golden morning light turns viridescent through the leaves as the sun follows Jarold’s path. He keeps a mental map of a half dozen secluded spots to tuck himself away when possible. A heather meadow for a nap; the northernmost stream for fishing; a sunny glen to read. These remain his until he sees or hears some brainless teens or a dithering gatherer stumble upon them.

With the morning’s stressors firing in his nerves, he heads to the most secluded: the westernmost edge and the mill abandoned by humans. It sits empty except for roosting creatures. The wheel, unmoving for decades, sinks piecemeal into the stream that once powered its toothy gears and grinding stones.

It’s never ideal to spend time in a human structure, of course, but this gives Jarold the greatest chance at remaining undisturbed. The gnomes didn't come here as a point of pride. Also safety, sure, but more importantly pride. Who wants human garbage? Certainly none need it enough to risk getting caught or injured. Moreso with recent intrusions of humans furtively laying traps and strapping strange little boxes to tree trunks. Worth the risk for a little alone time, perhaps, but not for anything else.

Jarold steps into the crumbling mill with more trust than the floorboards garner. His mind already rests in the second story alcove with picturesque, strategic views to the west of the flowering prairie and stream and to the east of his familiar forest.

Before he can creak the first rotting stair, Jarold freezes. Glimmering behind the open-backed staircase are two eyes nearly indistinguishable from the shadows. He releases his held breath and mentally marks off the spot from his solitudinous sanctuaries. Incensed, Jarold steps toward the stairwell to castigate this rotten intruder. A number of things happen very quickly as he closes in.

The eyes, level with Jarold, smoothly ascend until they are nearly twice his height.

Before Jarold can haul his heart from somewhere near his feet, a crack of enormous doom sounds behind him.

His head whips around to see another tall being. One green-panted leg is consumed by moldering floorboards. She swears and wrenches her way free, coughing out dust as gray as her shirt. Beneath a wide tan brim, dark eyes widen with shock upon seeing Jarold. Feeling is mutual at least.

“H-hi?” stammers a smooth alto voice from a friendly walnut-brown face.

Jarold bolts.

The only clear door is blocked. The windows are too high for gnomish legs. His only option is the staircase. Jarold abandons all propriety. He springs four-limbed up the stairs, feet and hands pushing him from the uncertain situation. He ignores the calling voice. He dodges a branch — OH NO THAT'S A HAND — in between the stairs. From the landing he throws a side table down the steps to hopefully slow the tall ones.

Below the staircase, the stranger pulls their hand back slowly and sways against the wall. They didn't think the little one a threat, but the other looked human. Enough of those today. They glide serenely back into the deepest shadows as the human focuses on the clattering above. For now, they would only observe.

Stella debates whether this is a teen with a spot to party or one of the strange hazing rituals her new wildlife reserve colleagues keep inventing. She pushes aside the echoing thoughts of campfire folklore and mutters about these damn kids.

Stella keeps her tone light, “Uh, hey? Buddy? Does your mom know you're here?”

No reply. “All right, I'm coming up. You're not in trouble, by the way. But it's not safe here. I'm — oop — going to help you outside.” She looks up in time to dodge a termite-ridden chunk of wood. “HEY NOW. Ahem. Please don't throw anything else!”

An irritated, adult-sounding voice calls down, “I'm not a hu- CHILD!”

“Oh! Okay, sir.” She stops with slight relief. “Can you please help me out and leave? I don't want to write a report anyway so I'll just pretend I didn't see you here.”

“…Go away. I'll leave.” He sounds a bit scared. Maybe he is just a kid?

“Fantastic! What's your name?” She starts picking her way down the sketchy staircase.

“For your report?” Gruff again. Stella feels she’s not winning this one over with civil servant hospitality.

“Ha, no! I really do hate reports. I'm Ranger Stella. Just joined this park a couple months ago.” She posts herself on dependable stone flooring and waits. Eventually she sees a small figure wearing a blanket clamber over the table with greater difficulty.

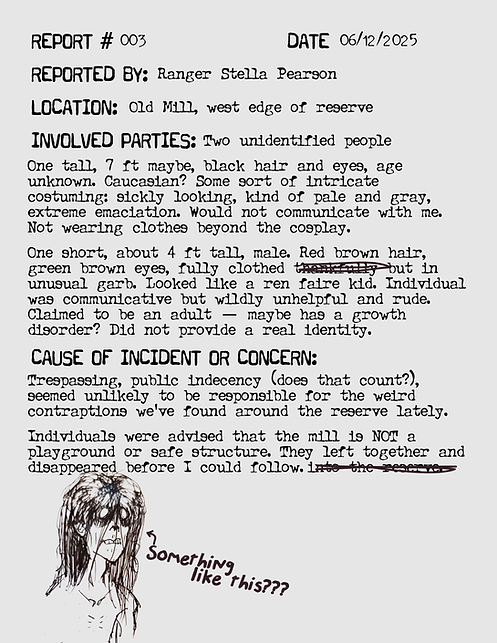

He looks unhappily at her as he approaches and brushes off brown linen trousers. Not a blanket: a cottony green cape sweeps over suspenders and off-white sleeves roll over tanned and freckled arms. Sharp and haggard hazel eyes cut from under a wavy mop of auburn hair.

Standing together brings attention to their height difference. He is no taller than an 8-year-old but bears the face of a man in his twenties. Rustling draws their gazes again to the staircase.

From beneath a deeply shaded recess, a person-shaped figure steps into a beam of stark midday light. Stella reels. Their skin is grayish and dry, almost ashen, and clings tightly to their bones. The face, well above hers, is concealed in an inky black curtain of hair save for two glinting eyes. A wave of familiar petrichor wafts along with them, followed by something equally pleasant but unplaceable in this context.

“This, um, is a cool costume. You Lord of the Rings fans? Kinda tall for Gollum.”

They both look confused and shift nervously on their feet, eyeing the door.

“Okay, whatever you kids are up to, just… Keep the LARPing to the designated campgrounds and trails? This structure is not suitable for humans.”

“AHA HA HA YES, we humans will do that! Come on. Uh, Goggim.” The grumpy one grabs the tall being’s hand and strides to the door. “Okay bye please don’t tell anyone you saw us.”

Stella watches them scurry into the forest, presumably back to their campground. First the weird conspiracy nuts grilling her about bigfoot or whatever and now nerds. She might have to make a report after all, just to let her peers know to keep these dorks safe.

Jarold had a long, quiet walk back to Oakvale with the stranger. He was too shaken to try beyond a few cursory questions with no answers. He had to spend his remaining wits keeping the other moving. Moon above, they poked at everything that caught their gaze!

They were obviously not human to anyone with even passing awareness of the hidden world but didn’t seem familiar with the woods. Mostly gnomes populated this area, occasionally a travelling fae merchant visiting from other realms. Jarold couldn’t place their species. For now, he simply called the eerily silent being Cryptid. With no desire to draw human curiosity, they had to retreat to the village while a plan could be made.

Now, after what feels like hours of repeating the tale to Uncle Benton, the mayor, council members, and anyone that stopped his path, Jarold sits at the back of an emergency town meeting. The township argues around them in fearful tones. Cryptid glances around curiously and picks at items within reach. Jarold has sore legs, a sweaty brow, and a headache.

Although the situation is potentially quite serious, Cryptid seems unperturbed now. Uncle Benton raises his voice above the commotion.

“We cannot, above all else, let our home be discovered by those brutes. I say we keep, er... the esteemed visitant? In our care until the danger passes.”

“And WHO do you propose takes this person — it is a person, right? — into their home?”

Silence fell over the group, enough to give Jarold an unrealistic level of hope that this might end soon. Maybe they could let Cryptid go deeper in the forest and be done with this. Jarold could return to his pleasant — no. Well. Quiet life. Avoiding others. Being by himself. Yes. Great. Hm. Perhaps...

“Oh for chestnut's sake! I'll help them.” No one is more stunned at the announcement Jarold made than himself. The quiet discomfort redoubles into shock. “Ah. The human. She didn’t follow. Tomorrow they, uh, they'll — we can figure something out.”

Jarold looks at his uncle for the first time ever in his adult life with a silent plea. His overbearing uncle will likely jump at this chance to prove the familial bond to Jarold. But Uncle Benton’s gaze is too low to catch. Jarold follows the angle to see arching fingers, pale fading to blackened tips, gently folded around his hand.

“A great go-getter, my Jarold!” his uncle recovers. "We'll host our guest at the Cloverspark home, plan for a safer outing with the sun's return." The shock and fear in the crowded hall softens into murmurs.

With no objections or eager volunteers, conversation turns to practicalities such as reinforcing the hidden pathways with camouflage and lookouts, and to impracticalities like what kind of main course the celebratory feast should have once this all blows over.

Jarold, hand still enclosed by Cryptid's, backs them slowly out of the crowd. Can't really go unnoticed after his moment in the spotlight. Or when pulling along a seven foot nightmare. His uncle trails after as he makes polite excuses to the neighbors. Jarold senses a conversation coming with him.

But with the crowd miraculously parting around them, they make it to the Cloverspark household before Uncle Benton. Jarold immediately sequesters them in his room. Say what you will about his uncle, but the man respects his boundaries. Enough arguments and fights have made this space unbreachable to his family.

Cryptid seems unbothered by the constraints of having to kneel in gnomish rooms. They snoop through Jarold's bookshelves and hold fabrics up to their face for closer inspection. Oh no, are they smelling it?? Jarold yanks away a linen shirt as he sees, with horror, a tongue poking out of the curtain of oilslick hair.

“Do not lick my things.” Cryptid's head turns toward Jarold but makes no expression — no anger, nо remorse. They shuffle on their knees back to rifle through the beleaguered bookcase once more.

Jarold is at wit's end realizing he's volunteered to care for a towering toddler. He needs to distract Cryptid for the safety of his complete collection of novels painstakingly traded for over six years of tedious markets.

“You can borrow a book tonight, just... Be careful, please? I don't lend them out usually.” Cryptid looks again at him. Their head tilts.

“...Can you read gnomish?"

Cryptid looks at the open book on the nearby desk. They crane over. They look up and shake their head.

“Can you read English?” Jarold points to another book.

Cryptid squints at print once more. Looks up, shakes their head. Fantastic.

“— ! Jarold! I made your favorite! Come on, sleepyheads!” A bell-like voice tinkles down the hallway to the open bedroom door. He grumbles sleepily but can’t resist the syrupy, savory smells. Oh! Mama made sausage and her special wheatcakes! He hasn’t had that in —

He watches carefully from one of father’s knees as sturdy, warm hands twist string and feathers delicately into flies. No fish can resist his lures. No one beat his record catch until after he —

The sunlight blankets his back as he carefully fills the oil crayon petals with a rich blue. Uncle Benton brought these art supplies but made him promise to share. She was drawing a fish for their father. His mother loves forget-me-nots. She loves them so much that he brings them every year to her —

Papa makes the funniest voices at bedtime stories. But he is too good at the usual tales and we want to challenge him, so we are writing a story for him to read to us. It has a friendly dragon protecting a family of talking mushrooms from a hungry human. She wants the bad guy to be a bear, but I tell her humans are way more scary and I’m right because I am her big brother and I will always protect Silvia —

Jarold inhales and sits up crookedly. His right arm is all needles from laying on it wrong. It takes a minute to get his balance and breathing right again. This is his room now, in his uncle’s house. His house is gone, and his family lays together. He thinks maybe the dream lingers, smelling the soil of their graves: but this is a darker, greener soil. Jarold’s eyes adjust enough to see Cryptid laying on the floor, head at one wall and feet at the other. Poor creature can’t fit upright in here and barely fits sideways.

He gently treads to the window and sees the sparkling sky easing into light hues at two points on the horizon. The periwinkle edge of sunrise radiates to the east while embers of a human town set the southern edge ablaze. Early, but he likes the solitude. Better to start his day now than see if the dreams slide to harsher memories.

As he picks his way around the room and eases drawers open for fresh clothes, he feels a prickling on his neck. Jarold peeks over a shoulder to find a familiar glint in the shadows. He realizes that Cryptid has been watching him from their repose.

“Mercy! Have you been awake all night?” he whispers.

Cryptid sits up and leans one arm against a bent knee. No, they shake their head. Before Jarold can ask the next question, they rasp, “Bad dream?”

Too surprised to question this newfound voice and too tired to brush off the question, Jarold replies quietly, “Good dreams, actually, but they never stay that way.” Perhaps this is the only chance he’ll get for answers. He slowly sits on his bedside facing Cryptid. “Did you? Have dreams?”

Cryptid brings their other knee up and wraps both arms around their legs, a whisper of the dry skin brushing over itself like autumn leaves in a breeze. “Yes. Not good dreams.” Jarold can’t discern their expression in the dimness before their face sinks a little into their arms. “My home. It’s far. Lost.”

Jarold feels a sympathy he rarely spares for his insipid neighbors. Most of them can’t fathom what it is to be ripped entirely from your home. He’d moved beyond shock and numbness in his grief to irritation at their constant empty platitudes. He didn’t notice when exactly the feeling morphed into contempt. Now it is more comfortable to keep them all at arm’s length than to struggle against their pity.

“I… I actually understand.” Cryptid raises their head just enough to meet his eyes. Jarold swallows against a bitter lump. Not the time to be tearful. “Maybe we can get you back. Do you know how you got into this forest? I’m sure I’d have noticed folks like you around if you were local.”

Without uncurling, Cryptid offers, “Ran from the city.”

“THE — the city?” Jarold catches his shocked outburst before he wakes his nosy uncle. “You’re from the human city?”

Cryptid shakes their head. “Weird light. Woke up there. Humans screamed.” They hug their knees tighter. “I ran. Some followed.” The memory sounds as painful as their grating speech.

“Say, what should I call you? I’ve, er, sort of named you in my mind thinking you’d never talk and that seems rude now.”

Cryptid perks up, unfurls their spindly limbs to sit cross-legged, and gently clears their throat. “At home, I’m ℘̵͕̋͜ơ̷̭̪͛͘ʂ̷͓͋̒ʑ̶̞̙͑ų̶̻̃ƙ̵͍̮́ı̶͔̎ῳ̶̻͓͛͌ą̵̩̖̋̒ƈ̴̹̱͋ʑ̴̞̏ ̷̦̾̈́ơ̴̦̰̅̇℘̸̰̈ơ̴̪͌ῳ̶͖̃͐ı̵̜̜̈ɛ̸̞͘ṣ̶́͗̋ƈ̵̱̅ı̴̮̅ ̷́̉ͅ.”

There is a discordant ringing in Jarold’s ears and he feels like a nosebleed may follow. Jarold understands now why his own language sounds so painful for Cryptid to speak.

“Please never say that again.” They slouch. “Ah, I mean, I’m sure it’s lovely? But also I think it doesn’t quite hit gnomish ears the same. And I can’t make any of those sounds, not without damaging something inside me. Can I perhaps offer the name I’d picked?” They look a little deflated but nod.

“Cryptid? Is that acceptable?”

They tilt their head in thought. “Cryp… tid? What is the meaning?”

“A cryptid is… a sort of mysterious creature that may not even exist.” Cryptid looks affronted, so Jarold continues quickly,

“Sometimes they are magical, or even dangerous. They are rare and special. I confess it’s a human term, but I quite like it and I think it suits you.”

There is a barely perceptible yet entirely genuine smile. With as much warmth as they can intone in this garbled language, they respond, “Cryptid. I accept.”

Clockwork Princess

by Harlow Brightheart

Once upon a time in a kingdom crystalline

there was a king that was obsessed with time

He wanted a child who would be the same forever

So he set himself upon mechanical endeavor

A skeleton of melted crowns and gears he stole from clocks

He made himself a daughter and his court a music box

Gears propelled by crystal heart, she danced precise and stately

Charged with fragile monarch, the court turned obligately

Clockwork Princess had no eyes, no ears, no voice to call her own

Air whispered against polish as she spun obediently alone.

The wind upon her rivets sent her ticking off the charts

Zephyr against her face plate made her yearn for softer parts

She tried to catch the feeling, leapt out of step with court

No longer keeping to the music, the wind her true consort

Unabashed and joyful she tried to touch the sky

One step too quick she tumbled, for a second she could fly

Gears scattered on the floor, apparatic whine

The princess lay in pieces, crystal cracked to exposed spine

Though the King tried to rebuild her the result was amateur

Her star at court was fallen and replaced nouveau danseur

Hidden in a corner tower made of lesser rocks

The princess patinas behind many doors and locks

Her chassis is a coffin for what used to tick reliably

Tangled wires round her body tangled into bridalwreath

From high above a draft creeped in through cracks long sown

Around her toes a moat of dust rushed gently ‘cross the stone

Some tension deep within her jumped and gears began to start

Her love had come to find her and did not care about her marks

Fireflies

by Jules Darling

Oatmeal Cookies

By Cecilia Rose Dillon

á la a grandmother I never met

1. Cream together butter, white sugar, and brown sugar in a large bowl, beat in eggs and vanilla

Rachel had shown up unexpectedly at 11 o’clock that Wednesday night without so much as a call beforehand. Not that she ever called, she tended to just show up half starved with some adventure to tell that ended in an explanation for why she’d be needing another small loan from her brother, Loretta’s husband Mr. Robert Newsom. She had no mind for the hour, nor the fact that it was a school night. Not a single blessed care for the volume of her laughter or the clatter of the shouldered load of luggage she hauled through the doorframe of the Newsom’s cozy little ranch style. The little slice of normality they’d only just paid off the mortgage on.

2. In a separate bowl mix together salt, baking soda, flour, oatmeal, and coconut for that singular queer-yet-familiar flavor.

Loretta herself could not stand Rachel. Could not stand the perfume of cigarette smoke and oranges that clung to the air around her. The scent reminded Loretta too vividly of Christmas and hot punch dotted with floating citrus and clove. Mistakes, slick and tart that burned on the back of her tongue no matter how many cups she had gulped down in an effort to develop a taste, as every relative and godforsaken passerby of Jackson County had insisted she would. Her husband had continued to insist on the family tradition, reminding her whenever possible how much he loved her daddy’s mulled wine, but luckily last year’s disastrous party had convinced him to cut it off without further argument.

Rachel’s ilk traveled too often to be natural. She wore leather in all seasons, her heavily worn jacket soft as butter despite the jarring bits of metal and wording that crusted it. She wore her pins and beaded chokers like any decent person might have worn diamonds. She wasn’t fit for society, suburban or otherwise, and no amount of her ingratiating herself would convince the Newsoms to the contrary, as far as Loretta was concerned.

3. Add the dry ingredients to the butter mixture and mix until combined, adding nuts and dates if desired.

And yet, regardless of the fact that no one had asked for her, Rachel had appeared. Slept in the guest room on the other side of a thin wall from Loretta, who had been unable to sleep with this new fourth set of lungs breathing in the dark reaches of her home. She had laid there straining to hear those breaths, trying to separate them from those of her husband and son which she should know so well and yet couldn’t quite seem to tell apart.

4. Allow mixture to rest in the refrigerator til morning when it will be ready to be balled and baked.

Suddenly it was morning. The Kentucky air hot and heavy outside long before the milkman’s cart had clattered in and out of earshot. Bob had gone to work early, their son Richard trailing behind not long after him. The boy’s tightly bound stack of schoolbooks dangling so low on the leather strap that it brushed the ground with each pendulation of his arm as he slumped off to school.

Their habitual absence left Loretta at home. Alone. With Rachel of all people. Bless her, the girl—Rachel was 3 years Loretta’s elder, but a girl nonetheless—was not much for company. She talked far too much, voice low and raspy until her first saccharine cup of coffee smoothed her drawl into a low rumble. Like stones moving. Her stories were distracting, often making Loretta lose track of herself as she mopped the same spot in the kitchen for near ten minutes, Rachel leering at her over the gleaming Formica countertop. It felt as if the girl was doing it specifically to throw off Loretta’s carefully maintained routine only to smirk knowingly at her sister-in-law’s discomfort.

“You doin’ alright there, Etta?”

Yes. Loretta was fine, thank you very much, and she’d be doin’ a whole hell of a lot better if the good Christian name her mama had blessed her with was being used when addressing her.

5. Divide into equal sized lumps about one inch wide.

The brand new top of the line air conditioner Bob had installed two summers back whining and spitting at the stifling air it was expected to soften. Choking on yet more heat as the oven blazed in preparation for the small army of oatmeal cookies currently being wrestled into shipshape by their commanding officer. Richard’s favorite, she thinks, though maybe it’s Bob who likes the coconut.

Loretta’s fastidiously manicured nails won’t abide something as filthy as reaching into a bowl of dough to shape it, letting it cake into the creases of her knuckles as she yanks clumps of the chilled slime free in the sweltering room. Instead she hovers over the bowl, dripping glistening sweat into it as she painstakingly smoothes a measuring cup full of the ick with a rubber spatula and then scoops it back out and onto the oiled pan without laying a finger on it. Just as God and her own mother had intended, even if the heat meant the dough kept sticking to everything under the sun and making the entire process nothing short of hellish.

She pointedly ignores Rachel, who was talking in that frustratingly low, calm voice of hers like she isn’t dying of the heat just as much as Loretta is. Telling stories on this ‘n’ that and dropping thinly veiled suggestions for improvement on Loretta’s methodology. She’s not going to be chased off, apparently, because after ten minutes of watching Loretta sweat and curse the process she imposes upon herself, Rachel starts with a smoky, "there's an easier way to do this, Etta, babe."

Rachel sticks her own clean but unadorned hand directly into the dough, scooping out a chunk of it and wadding it up between her hands before placing it next to Loretta’s painstakingly positioned lump. Its smooth and centered, and only the slightest sheen of butter and sugar remains along Rachel’s long, calloused fingers until she laps the residue away with her pink tongue.

“See?” Rachel teased, reaching back into the bowl for another go.

Loretta slapped her hand away, “Girl, get that spit-drenched paw out of my bowl ‘fore I smack you so hard you think the ground flew up and hit ya.”

Rachel laughed, the sound throaty and genuine, as she pushed her hand back in and continued to help.

6. Bake at 375* for 10-12 minutes, remaining vigilant so as not to overbrown them.

No one seemed to be home when young Richard slouched in from his day. Unexpected, what with company in the house, though not unusual. The young boy noticed a pile of hastily stacked cookies on a plate waiting for him, and ran excitedly towards them before noticing their texture and coming to an abrupt stop and pulling his lip up into a disgusted sneer. He was working up the lung capacity to holler out a complaint to whoever might hear him when he realized...

Oh.

Of course.

Aunt Rachel was visiting so mom had made those god-awful coconutty oatmeal cookies of hers that no one other than his mother and his mysterious and under-discussed aunt liked. This batch had burnt a little on the bottom, as they always seemed to do. Oh well, he thought, at least someone else will eat them. He stuck his head in the fridge to see if his mother had left anything else for him, and did not come away disappointed.

Pride & Joy

Sara Rani Reddy

Mina was left in a vague state between sleeping and waking as the wisps of her dream began to dissolve. She could hear the floorboards above her creak. The rhythm of the grating noise was steady as a metronome. After a long night of writing, she was not ready to begin the day. She turned over in bed, burying her face in the thin pillow, wishing that her sisters upstairs would quiet down. They were seven and ten years older than her, but they certainly didn’t act like it. Her arm reached out for the bell to call Rosie, who would surely get Amara and Vera to hush up. As her fingers rose, they found not the cold brass of the bell, but damp, crumbling drywall. Mina jolted upright, folding her legs underneath her to sit up and face the back wall. The wisps disappeared, leaving her alone in the cramped boarding room.

Her eyes traveled from the water-stained wall up to the broken plaster of the ceiling. She rotated on her knees, spinning to face the rest of the room. She slid out of bed and onto the stool by the small desk, illuminated by the gray morning light flowing in through the barred window. Her cotton nightgown, sticking to her from the summer heat, caught on a splinter of the bedframe, though she didn’t notice. There was nowhere to go to feel the tug of the snagged fabric. There was barely room for the two valises she had packed, wedged between the bedframe and the door. But Mina was glad for this—she hadn’t had enough to rent a padlock for the door.

She listened to the distant doors slamming, voices yelling, children crying. Her eyes drifted across the desk, strewn with white paper covered in dark ink, a matchbox, and a half-melted candle. She shook her head, surprised that, even for a moment, she had thought this was home. Flipping through last night’s pages, her foot tapped to the rhythm of the floorboards creaking. No, she thought, I’m surrounded by strangers here. Her head rose at that, and her foot stilled.

It’s not that different from home after all.

Mina turned that realization over in her mind. It was pithy, even if it was not quite true. She reached for the heavy, gold pen on the desk, her fingers sliding along the smooth, mirrored surface to remove the cap, and scribbled the thought down on one of the papers she had taken from home.

No. The house.

At the house, she was known. She was loved. Despite it all.

Now, she was a stranger to everyone around her. When she had entered the boarding house the day before—the fifth one she had tried—Mina had been relieved when the landlord granted her a room. She hadn’t yet learned to tune out the wide-eyed stares at her skin, at her hair, at the slight accent that creeped back into her voice the more scared she felt. Now, sitting in the safe solitude of her room, she nervously played with the cap of the pen, recalling the expressions on those faces. She didn’t remember it being so overt when they first moved from Udaipur to New York. But it was easy for a young girl to ignore the differences when she had her mother’s hand to cling to, her sisters’ example of silent strength to follow, her father’s stare to quiet any voices that would dare speak against them.

She used to love that about her father, his imposing nature. As a child, she had felt safe behind the walls he built between her and the real world, leaving her free to grow and play and live and study and write. The walls that had kept their family safe as they crossed the ocean and settled in America, into their new lives. Within those walls, he had brought a group of friends to replace the uncles and aunties they had left behind. But the walls hadn’t kept the danger out. As she sat in her chair, thinking, she felt herself tense. The danger had still gotten to her.

Mr. Wh–

Before her mind could summon his full name, a wave of nausea crashed over Mina. The image of him swam before her. Though the bruises had long since healed, the capillaries in her arms burned like they were bursting anew.

Mina pushed the memory of his pale face away, back behind the gates, behind the walls, hidden behind the boxes of memories of playing with her older sisters, of twirling in the beautiful dresses that she would never again wear, of thumbing through the gilded books she would never again touch.

She had only left the day before. But Mina felt as if she had been gone for years.

She had planned it. Planned the day she would finally ask her mother—when her father was away on business. She had planned what to take. Reams of blank paper. And nothing to remind her of that place, of that truth.

Nothing, except the pen.

Everything she had ever written, she had written with that pen. Her father had given it to her the day they arrived in New York. He had knelt, telling her that she had nothing to fear, that he would always be there to protect her. But if she needed something to hold onto, to keep her steady, she could hold onto that heavy, elegant pen.

It had been her anchor. Even after bringing the recording to her mother and learning the truth about her family. As Mina prepared to leave the house forever, she couldn’t stop herself from taking the pen.

An hour later, she had grabbed her two valises. Mina had walked past her crying mother, past Rosie whose arms were clasped around the matriarch, past the threshold made of wood imported from India, past the grounds where she had played make-believe, past the gate, the gate that had kept everyone out but let the most dangerous one in, the gate with the spiked wrought iron bars that had scared her so much when they moved there. Past the porcelain roses that her father had commanded be added to the spikes. Past her home. Past her life.

Now, Mina sat looking out the window of the boarding room, waiting, numb. Her mind stuck in the past, in the same moment, playing it over and over again. The sound of a loud car horn from outside brought her back to the room before her. But the fear remained, as it always did, and turned into paranoia. She threw a glance over her shoulder at the door, imagining her father bursting through it and carrying her back home. What if someone had seen her come here? Someone who knew her father? No, he’d be here by now if they had. Wouldn’t he?

She considered the window in front of her. The room was on the second floor. If someone was searching, could they see into her room to find her? She shuffled to the door and wriggled one of her valises free, opening it to remove one of the few plain dresses she had packed. As she returned to the desk, she pulled out the drawstring from her nightgown, tied its ends to the bars of the window, and draped the dress over it. The makeshift curtain enveloped the small room in darkness. She felt her way back into the chair and groped around the desk to find the matchbox. The match hissed, and a dull pain settled behind her eyes as the small stick ignited the candle’s wick, the light growing brighter.

Mina sat still, staring at the lambent flame. Her shadow jumped around the wall. She turned to look at it, at its frenetic movements. That shadow that obeyed the candle, not her. She picked up the pen.

*

The sun had not yet risen when her eyes opened. The rhythm from the floorboards and doors of the building played in the background as she alighted from the bed, shuffling along the narrow paths between the frame and the walls. She lit the candle on the desk, then looked up at the crisscrossing clothesline on the ceiling, supported by three-inch nails she had hammered into the crumbling walls. She gently removed a plain black walking dress and readied herself to leave. Plaiting her long black hair, she rolled it up into a bun before grabbing her coat, scarf and gloves, her key, the pen, and the stack of papers that waited patiently on her desk. She blew out the candle, then shuffled to the door, removed the padlock, and swung the door open.

The sounds of the building played at full volume.

It had grown quieter in the winter, but the freeze in the air agitated the residents just as much as the summer blaze.

Mina turned back to face her small, chaotically organized room, making sure she hadn’t forgotten anything. Then she closed and fastened the padlock on the outside of the door, jumping slightly as she always did when the shackle thunked into place.

Twenty minutes later, her hands shoved in her pockets, her right glove nestled against her papers and the smooth cylinder of her pen, she walked down the alley to the restaurant.

She yanked open the rusted door, which wailed as she stepped through. Everyone but Abel looked up. The four servers and two cooks greeted her with polite smiles and continued preparing for the day. But Abel kept his eyes on the ledger laying open in front of him as he stood in the middle of the kitchen, an obstacle that the others navigated wordlessly, making sure they didn’t get too close. Struggling to carry a crate of potatoes to the sink, Nico managed to duck just in time as Abel’s elbow flew up to run his pale, wrinkled hand through the remaining tufts of straight, white hair. Mina exchanged a look with the shaken Nico as she doffed her outer layers, depositing them on the coat stand. She could just make out the sounds of the restaurant as it came to life. The clatter of the door, the clink of the silverware, the grainy music pouring out of the phonograph in the corner by the window. No doubt the sun was starting to shine on the dull, brassy surface, just as it had when she heard it play for the first time.

She felt herself stiffen as the boxes in her mind began to shift. She slipped her hand into the right pocket of her coat one more time, reaching past the paper to touch the pen, its cold solidity bringing her a sense of calm, before she walked over to the stack of dishes to be washed from the morning’s preparations.

*

After the end of the lunch rush, the cooks were closing up the kitchen when Mina finished drying the last plate. She balanced it at the top of the stack of clean dishes, wiped her hands, and walked to the corner by her coat, perching on an upturned crate, sliding out from her pocket the bundle of papers and the pen.

There was a faint metallic chime as she uncapped the pen and poised her hand above the pages. She sat still, staring at the chipped edge of the sink. Then her hand began moving. The letters on the page sketched the images playing out in her mind. The plates that had come through the door. Which plates had barely been touched. Which plates had been licked clean, not a drop of gravy left behind. Who the people were. What their lives looked like. She let her imagination run off into the distance, brought back to her surroundings for just a moment when the two cooks waved their goodbyes. She sat in the peace of the empty kitchen, her hand cramping as the words flowed. But desperation pushed her through the ache, a fear of losing the words in her mind.

When the door to the dining room flew open, announcing Abel’s entrance, she jumped, at once forgetting the pain. She rose to attention, emerging from her corner to face Abel.

“You’re sitting down? I don’t pay you to sit on your—” His eyes traveled to see the stack of clean dishes.

Mina felt her mouth resort to its comfortable, awkward half-smile as she stood silently, resolutely, watching the old man brush off any shame to step closer to the dishes, inspecting her work as he did every day. He nodded, still looking away from her, putting his hands in his pockets. He glanced back as Nico came through the door and squeezed around him to bring three plates to the sink. Mina raised her eyebrows at the dishes and looked at the young boy.

“They took forever to finish eating,” Nico said, rolling his eyes, letting his accent back into his voice in the privacy of the kitchen. Mina capped her pen and deposited it into her coat’s cavernous pocket before stepping to the sink. Nico turned, jolting to see Abel still standing there, looking at him. He skirted the imposing octogenarian and rushed to grab his coat, calling out goodbye as the back door swung shut.

Mina got to work on the dishes as she waited patiently for Abel to speak, knowing that he would start talking in his own time. He was very sparing with his words. That was the first thing he had taught her about her own writing. Don’t waste words. Don’t waste my time.

“I looked at the draft,” he huffed, years of smoking cigars weighing on his voice. On the narrow counter of the sink, he dropped a stack that had once been crisp, white paper. The rectangles hung limply, no longer able to hold the weight of the red ink covering the black of Mina’s words, in addition to smears of ash and blotches smelling of whiskey. She smiled as she dried her hands and reached for the papers.

“Fast,” she said, impressed to get back the draft she had presented to him only two days ago.

“Better,” Abel said, trying in vain to hide the pride in his voice. Mina met his gaze and grinned as she brought the manuscript to her chest.

He looked down, shaking his head dismissively as his hand reached into his breast pocket to retrieve her wages for the day. She watched, amused as he went through the ceremony of counting out the small bills, holding them out to her, before suddenly retracting his hand, removing the topmost bill to return it to his pocket.

“For th—” Abel began.

“For the edits,” Mina interrupted, having grown used to, and even fond of, this little dance he insisted on each time he returned her writing. She held her hand out, and Abel placed the money in her palm.

“Plans for the rest of the day?” he asked, slipping into his paternal tone, the same interrogative voice he had used with his own children decades earlier.

She threw him a pointed look, walking over to place the money and the precious papers into her coat. She collected the loose pages she had been writing earlier, organizing them into a neat stack before slipping them too into the now-bursting pocket.

“I know, I know, back home to write.” He waved his hands, starting to turn back towards the door to the dining room. She bristled at the word home to describe the place she had been living in for the past seven months. He turned back to her.

“You should get out more, kid. Going from your place to here and back—it’s not living. You’ll run out of things to write about.”

“I don’t know,” she countered, walking back to the sink, “what little life I have, it’s got more than enough drama to fill a dozen books.” She smiled weakly and looked at him.

Was that guilt on his face?

This man who had unwittingly upended her world.

This man who was helping her to pick up the pieces.

“I’m glad I know,” Mina said as she looked Abel full in the face. “I’m glad you showed me.” She was surprised at the words as they came out but felt a surge of relief and calm as she heard them in her own voice, and she knew that they were true.

Abel turned away quickly and pushed through the door to the dining room. She took that as his goodbye and swiveled to finish washing the plates. She heard the hinges of the front door of the restaurant creak over and over again, and she knew that his other business was now open. What stories and secrets were being traded on the other side of the wall?

After a few minutes, the sink empty, the dishrags washed and hanging to dry, Mina slid on her coat, scarf and gloves. She stuffed her hand into the right pocket to feel her wages, her manuscript, the pen, and her loose pages as she stepped out into the alley.

Mina had just turned the corner to reach the main road when she collided with a pile of purple taffeta.

“Oh my goodness,” she cried, quickly getting up from the path to reach out to the woman she had run into. She needn’t have bothered—the two men walking with the lady had already begun to haul her and the dress up. “I’m so sorry, Miss.” Mina patted the pen and papers in her pocket to check that they were safe, then looked around awkwardly as the woman muttered and brushed away the dust from the ruffles of her dress. Mina’s polite society manners wrestled with her newfound don’t-stop-just-keep-going policy. Should she stay? As the woman’s face came into view, between an enormous hat and the high collar of a bright dress, Mina wished that she had walked away.

“You should really watch where you’re going, y—Mina?” the woman’s voice descended from its haughty indignance to a familiar tone.

“Anisa.” Mina scratched her forehead.

“Wha—it’s good to see you.”

Mina’s hand dropped, and she registered the genuine concern on the face of this girl, still living the life she used to have. Anisa stepped away for a moment to whisper something to the two men, who then strutted down the path to the black automobile waiting for them. Mina watched them walk away, their coattails swaying in the gentle wind that carried the smell of food and smoke. She looked past them at the bustling crowd in the square of the neighborhood and was surprised when Anisa grasped her arm.

Mina looked back at her, this person with whom she had grown up. They had spent every weekend together as their parents socialized, humbly climbing the ranks of the social ladder, diminishing themselves as needed to bypass the judgment they faced as immigrants, only to swell their chests and beat back those who were now their underlings and who dared to question their Americanness. As their parents worked together, they assumed that their children would form similar partnerships. Mina had tried. And she knew that Anisa had tried too.

On paper, they should have been best friends. But something hadn’t clicked.The two girls had made small talk at the afternoon teas, dinner parties, and social outings. Left alone as their older siblings moved ahead, laughing easily. The polite pauses and careful eye contact, the awkwardness that should have fallen away after their first meeting—it all remained. So, at every tea, every party, every outing, Mina would play her part, smiling appreciatively at Anisa’s surprisingly insightful comments while judging every movement, every syllable, every crease of her dress.

As she stood in the square outside the restaurant, looking at the woman she had never managed to befriend, Mina’s eyes drifted to the reflection staring back in a shop window. Before she could get a good look at that plain, unadorned person standing small, Mina brought her gaze back to Anisa.

“It’s so good to see you,” Anisa repeated, a hesitant smile growing on her face, her arm hooking around Mina’s, directing them to amble slowly down the path. Mina let herself be led forward, unsure of what to do, or how to navigate the sensitive matters that Anisa would no doubt try to investigate.

Mina felt the familiar instinct to redirect the conversation, to shut down any potential scandal, to protect the family, until the shame and anger boiling in the pit of her stomach protested, and she remembered that those people were no longer her concern.

Or were they? In her confusion, Mina decided to keep silent. That was the safest path.

Anisa’s large dark eyes searched Mina’s, and Mina looked down at her feet. She proudly kept her simple black shoes looking shiny, but even with all the shoe polish in the world, they didn’t hold a candle to the bejeweled heels beneath Anisa’s feet. Mina looked at them, imagining the hand that had spent hours stitching each gem to the satin fabric. She knew that these shoes were not made to be walked in, and suddenly felt more like a walking stick than an old acquaintance being embraced. Mina turned to face Anisa, pulling her arm back slightly.

“It’s good to see you, too.” Mina gave a perfunctory nod. Anisa waited to see if she was going to say anything more before launching into the small talk. Mina tracked the conversation in her mind, curious to see how Anisa would deftly guide the subject to the questions that she and everyone from their circle couldn’t wait to ask.

Anisa told Mina about her brothers, the two men standing by the car, Amar and Sameer, who just got back from London where they had finished their studies. Mina remembered how scrawny and timid they had been years ago when they left, their fair skin growing paler by the minute as their luggage was packed into the car to take them to the ocean liner. She turned back to see the confident, broad-shouldered men they had become. They didn’t shrink away from the crowd of people in the square, like they would have done as kids. Like Mina did now.

“And they’ve somehow picked up the English accent,” Anisa giggled. “I hope it fades away soon. I can’t help but laugh every time they open their mouths!”

“Your accent is almost gone now,” Mina said without thinking. She kept her eyes on the ground, willing Anisa to just move on. To not see the path that Mina just handed her.

“Well, I’ve been trying to get rid of it for years,” Anisa playfully exaggerated her r’s and softened her t’s to mimic the thick Indian accent she had carried with her on the boat. “I wasn’t as fast as you and your sisters. Mom finally decided to enroll me in elocution lessons.” Mina felt Anisa’s eyes boring into the side of her head. “The same woman your mom hired to be your family’s tutor.”

Anisa paused, and Mina could sense her counting out the seconds, waiting the appropriate period of silence before broaching the topic of interest. Mina marveled at this tact, this performative hesitance.

“Um, speaking of your mother,” Anisa started, and Mina prepared herself for the interrogation, but Anisa had trailed off, stopping in her tracks, halting Mina, too.

Now, this was playing into the moment a bit too much. Mina wished Anisa would just ask already. Why she was here. What happened. As she waited for the questions to come, worded ever-so-politely, Mina couldn’t help but look up and was startled to find tears welling up in Anisa’s eyes.

There was no shock, no horror. Just understanding.

Anisa didn’t know the truth, and even without it, she understood. Why Mina had needed to leave. In those tears, Mina saw herself.

Mina saw herself as the perfectly manicured hand reached out, and Mina saw herself as the dry, ink-stained hand accepted.

“I missed you,” Anisa said, a true smile growing on her face as the tears started to flow.

“So did I.” Mina let her own smile grow in kind, realizing the truth of the words. It was a reunion, but they were meeting for the first time.

From somewhere far away, the two friends heard a voice calling to them. They turned to see Anisa’s brother, Amar, waving, pointing to his wristwatch and then to the car. Mina felt Anisa’s grip tighten.

“What is it?” she asked.

Anisa’s threaded eyebrows knit together as she chose her words.

“We’re going to the press conference.”

Mina looked at her and shrugged.

“His press conference,” Anisa added, shedding no clarity on the matter.

“Who?” Mina started to laugh at the fear on Anisa’s face. “Whose press conference?”

“Your father’s,” Anisa said softly. Mina felt the tension flow from Anisa straight into her own veins.

“Uh,” Mina shook her head, “press conference for what?”

“You don’t …” Anisa’s eyebrows had come so close together that they resembled the unibrow her mother’s beautician had spent so long trying to remove. “Mina, your—your parents left after you did. They traveled to see Amara and then Vera, and then back to India. They just got back two days ago. And they arranged this press conference for the company when they got the news.”

Mina was starting to lose her patience with her new old friend. The anger on her face spurred Anisa to continue.

“When the news broke about Mr. Whitcombe’s death.”

The tension in Mina’s body congealed into searing pain, settling first in her arms.

“He was shot yesterday morning. It was in all the papers, Mina.” Anisa shook her head. “Come with us. To the press conference.”

Mina stepped back as the pain spread to her chest. She couldn’t speak anymore—it clutched at her throat before traveling down to the small of her back, then to her legs, up her shins, reaching for her thighs.

Anisa reached out, but Mina had already turned, running down the alley.

*

Mina found herself squeezing between two Indian men, smelling of sambar and paan as she tried to inch forward in the crowd. One of them was carrying a young girl on his shoulders, gently grasping her hands to keep her steady as she looked high above the crowd.

The spectators had separated into two sections; the white businessmen, there to hear about the fate of the company, and the aging immigrants, there to gaze upon their success story, their star.

Fifty yards ahead stood a large stage, upon which Mina strained to see the vague outline of an elegant woman in a cream-colored sari and a tall man in a three-piece black suit. His hair had started to gray. Her mother’s was as jet-black as the day she left. No, darker. She must have had Anisa’s mother’s beautician switch her to a stronger dye.

Mina did not register the pressure of the crowd squeezing in against her as her father approached the microphone to speak. He looked around the crowd, his bright eyes sweeping over their heads, making each of them feel as if they were truly being seen. She felt herself hunch over, bringing her head down.

“This is a tragic day for our city,” his voice boomed, embracing the r in tragic with his accent. Mina’s mind wandered away from the stage, remembering that argument between her parents. As much as any conversation between them had ever been an argument.

Her father had decided that his daughters and his wife would speak like Americans and ordered her mother to find a tutor. Her mother had asked when she should schedule his appointments, and he raged that he would never give up his accent. No matter how many firangi he shook hands with, he would be a proud Hindustani until the day he died. She remembered the way her mother walked away, without another word.

“An incredible man, with whom I had the pleasure of working for twelve prosperous years,” she heard her father say through the fog of her memories. Suddenly the fog shifted to the night of the party when her father had announced he was going into business with Wh—she took a deep breath. With him.

“My wife and I are shaken by his death, this titan who had such an impact on our life, and in whom I saw so much of myself.”

The fog shifted again. To that day in Abel’s pub when she had first gone to get his thoughts on her writing, when he had requested payment. She had brought no money to give him—her parents didn’t know that she was going to see him. So, he had asked for a secret instead. She looked around, confirming that the restaurant was empty before sharing the gossip she had heard Anisa’s mother whisper in the parlor—a scandalous extramarital affair within their social circle. Abel happily noted down the names, but he had held up his hand when Mina took out her manuscript.

“That is a juicy tidbit,” Abel wheezed. She held her breath as the alcohol and smoke wafted from his mouth. “But it doesn’t cover my fee.” Mina had started to protest when Abel held his hand up again. “I think we can arrange something to even things out.” She had felt herself stiffen on the bar stool, her legs pressed together, her fists clenched.

“No, no, nothing like that!” Abel said quickly at the look on her face. He shook his head, clearing his throat as he stepped back. “No, no. You see, I’ve got this box of records, audio recordings from one of my contacts in this business—he said the information on these could bring down a few powerful dynasties of people who are still fresh off the boat.” Abel raised his hands. “His words—he’s not big on immigrants, sorry, but in my line of work I can’t pick and choose who I work with.” He shrugged. “It is what it is, and the recordings are mine now. The problem is, I can’t understand a word. It’s all in Hindi.” Mina was impressed that he hadn’t said Indian, like most people would. Like most of her father’s own business contacts did. “If you can translate them into English for me, I’ll consider the fee paid in full.”

She had spent the next three hours perched on the same bar stool, having dragged the phonograph to sit beside her, listening to the records one by one and transcribing the secrets within onto the stack of thin sheets of paper Abel had provided. As she made her way through the pile of recordings, her eyebrows traveled up and down her forehead, learning intimate details of the lives of other families in her parents’ network.

Though the words were not her own, she felt like a real writer, sitting at the bar, gold pen in hand, its nib skating across smooth pages. Every now and then it shifted to the small notebook off to the side, where she scribbled down the most intriguing ideas for her own stories.

As she was putting the last disc on the phonograph, Abel pushed his way back into the dining room. She had smiled up at him, signaling that all was going well, sliding the stack of secret-filled papers towards him to peruse as she turned her attention to the final recording. By then, she thought that she had heard every conceivable scandal in the world, and her mind had all but wandered away, leaving her hand to thoughtlessly transcribe the words after her brain translated them from her mother tongue. Her wrist moved like an automaton, tracing out the names and the deeds mentioned.

But the automaton’s gears grinded to a halt at the mention of a name: Parvati Bhairava. Mina sat frozen, staring at the ink that had spelled out her mother’s maiden name, hardly breathing as she heard the panicked voices on the recording whisper her father’s name. Her eyes traveled to the top of the paper to read over the lines she had written without a thought.

They have to get married now …

It does not matter what match her parents had arranged before. After what this boy did, he must marry her now …

Why was she walking alone at night so close to that boys’ school? She should have known better. Anyway, she is lucky that it was such a smart boy. He’ll take care of her …

You, call Pandit ji and get the marriage certificate, write these names down, no, no, write it clearly…

Mina hadn’t realized that she was sobbing until Abel touched her shoulder. He had walked around the bar to calm her down. His concerned eyes scanned the paper before her, reading the small patches of ink that hadn’t been obscured by the blotches of tears. When he read the name on the page, his expression turned to shock, then to shame.

“Oh, kid … I—” Abel started then fell silent. He was never one to waste words. And he knew words could do nothing now.

*

In the crowd, Mina’s eyes jumped between her mother and her father, and she felt the nausea wash over her again. She gagged, doubling over. The men around her moved away, casting looks of disgust at her, inching further into the crowd in case she got sick. The cold winter air rushed into the empty space around her, and she took deep breaths as she stood up, her hand reaching for the pen to anchor her as she looked up. Mina’s eyes found their way to the hands clasped together. How could she stand to let him touch her?

The fog shifted again. To the day Mina left. Her mother’s silence when Mina played the recording. Her mother’s insistence that no matter how it had started, the love between Mina’s parents was real. Her mother’s heartbreak when Mina told her about the night of the party and what Mr. Whitcombe had done to her youngest daughter. Her mother’s recognition of the pain and the shame. Her mother’s rage when she learned that she had not protected her daughter.

“Sir? Sir? What can you tell us about the investigation into Mr. Whitcombe’s murder?” Mina heard the gaggle of press call out from the foot of the stage, her fingers clutching the pen, her eyes glazing over as she hovered between her memory and the scene in front of her. Her father looked from the journalists out into the crowd, his gaze sweeping over them once again before coming to rest on one spot.

“I will tell you that I always protect my own, and if anyone harms them, I make sure they pay.”

She heard the hardness in his voice, a tone he reserved for the discussions behind closed doors.

Mina looked up, expecting to see her father scrambling to recover from this lapse, this crack in his professional façade, but she saw only anger in his eyes. Anger and righteousness.

She felt tears drip down her face, her thoughts muddled and confused. Her cold breaths came out in irregular puffs. Sobs rocked her shoulders, and she knelt the ground, pulling her hands out of her pockets to steady herself.

*

Parvati’s eyes were fixed on her husband’s face as he spoke those words. She expected panic to bubble up to the surface, and she prepared for the struggle to keep it off of her face. But all she felt was grief. And fury. And the faint satisfaction that justice had been done. Even so, she felt herself drowning in the despair that it had come too late.

Parvati looked up at the crowd of spectators. Her eyes roved over the faces, gravitating towards the side with her people. In the distance, she saw a young girl sitting on a man’s shoulders, above the rest of the crowd. She remembered when her girls were that young. When things were simple. When she should have been paying more attention.

The young girl’s head turned away to look behind her. Parvati’s eyes followed to see someone pushing through the crowd. They were stumbling away, the people shifting around their staggering movements to press closer to the stage. Parvati found herself looking again at the young girl on her father’s shoulders. For a moment, the girl disappeared, her father lifting her off of his shoulders. Parvati felt the grief in her chest inflate until she came back into view, beaming from her father’s shoulders. Parvati stood on stage, holding hands with her husband as he lauded the guilty dead, looking at the child who listened to not a word of the speech, completely enraptured by the gold pen her father had just given her, laughing high above the strangers and the secrets below.